Digitising archives should not be for the purpose of preserving the information longer. Think over the last 20 years, or even 10, at how digital technology has changed. The Internet has evolved from a slow wired up service to something that can be used on most mobile phones, wirelessly and quickly. The Internet now is a hub for communication: there are more people on Facebook than the population of the USA. In terms of photography, over the last twenty years our digital cameras are becoming smaller and higher quality, and in fact, millions of images that are made today are from camera phones which are instantly uploaded and shared for global conversations on Flickr and Instagram. Digital technology has allowed us to document our society more easily and freely than previous generations.

The digital age in which we live is evanescent: every year a new iPhone is released. The platforms in which we hold photographs and data are fluid and everchanging. Do you have a VHS player to view old family videos? Information is bound by its distribution and these tools are changing rapidly. So why do we trust what we back our files onto when really we have to consider how in the future we have to update our storage systems so that we can continue to see the information. Archives are having the address this issue.

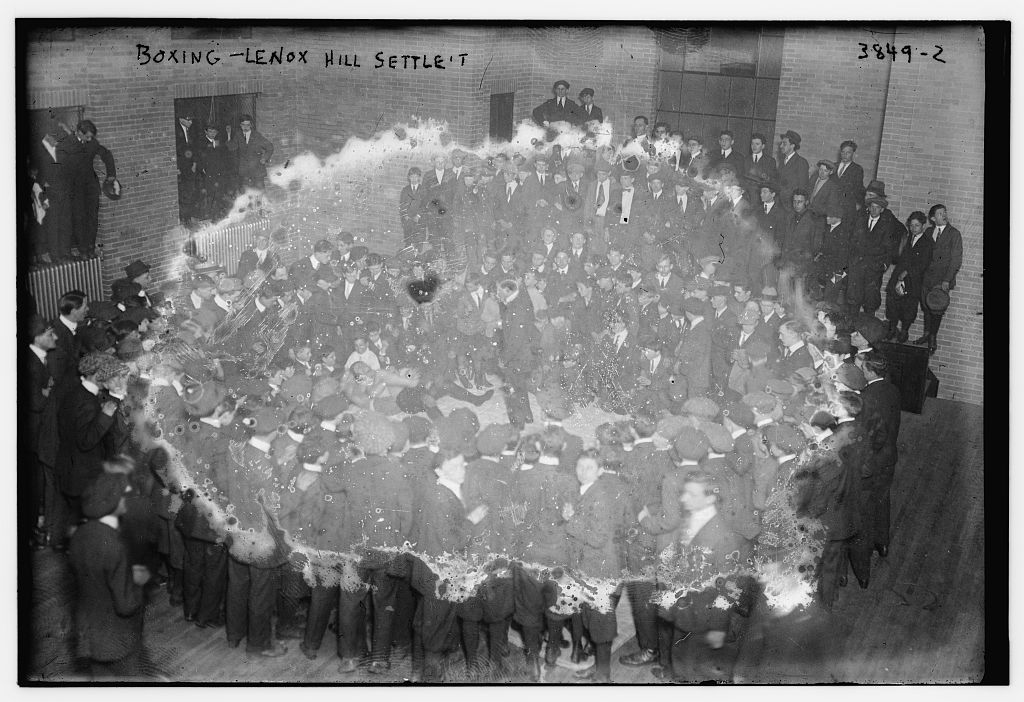

Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/12367638363/

The Dead Sea scrolls, made out of still-readable parchment and papyrus, are believed to have been created more than 2,000 years ago. Yet my barely 10-year-old digital floppy disks were essentially lost. I was furious! How had the shiny new world of digital data, which I had been taught was so superior to the old “analog” world, failed me? I wondered: Had I had simply misplaced my faith, or was I missing something?

This is the idea—or fear!—that if we cannot learn to explicitly save our digital data, we will lose that data and, with it, the record that future generations might use to remember and understand us.

So not only are we putting at risk historical digitised content, but our current content that we are making every day. The content in which we are subconsciously archiving for future use, or future generations to learn about the early 2000s. Today’s produced content is tomorrow’s historical document. D.J Cohen suggests that “the vast expansion of the historical record into new media that occurred between these dates presents serious challenges that will have to be surmounted if future scholars and the public are to have access to an adequate record of the past.”

This realisation of the fragility of files have had an effect in turn on digitising archives. James Billington from the Library of Congress recognises “we are in danger of losing history itself because the artifacts that historians have relied upon for centuries may not always be available when they are increasingly only obtainable in the more fragile, evanescent digital world.” Therefore, it is important that archives consider what is the purpose of digitising its archive because it should not be for preservation.

However, I have come to realise that digitised content is less likely to be lost if it is copied on different devices or Internet servers. Management of our personal files has in turn led to copying onto external hard drives and uploading to the cloud, to prevent this loss of data. Archives are adopting new platforms to share its photographic archives, such as Flickr the Commons. This means that there are high resolution files on a separate server, with no licensing to copy again and again. This is great, surely, but this dissemination of archive material, in my mind, isn’t necessarily a good means to keeping digital archives preserved.